history of

hayti heritage center

Hayti is

more than

a building

Since 1975, the Hayti Heritage Center has stood as a powerful testament to Durham’s rich African American history. Located in the heart of the historic Hayti community—a post-Reconstruction Black enclave that thrived through much of the 20th century—Hayti has long served as a guardian of cultural memory, community connection, and Black creative excellence.

Today, Hayti is poised to enter its next chapter—not merely as a venue or event space, but as an immovable cultural anchor of Black scholarship, art, and entrepreneurship. It is a living, member-supported institution that preserves Black cultural memory while fueling Black futures—redistributing power, resources, and opportunity through grantmaking, partnerships, and programs designed by and for the community it serves.

cultural commitment

We affirm that Hayti belongs to the people. Our commitment is to ensure that Hayti remains an immovable force—a center by and for the Black community, shaping a future that is as ambitious as its history is rich. We believe in cultural sovereignty: that Black institutions must not only preserve history but also generate wealth, power, and possibility for generations to come.

Hayti’s story begins with courage, vision, and resilience. In 1868, Edian Markham—a former enslaved person and African Methodist Episcopal missionary—arrived in Durham with five companions, determined to establish both a house of worship and a place of learning for a community denied access to either. On land purchased from Minerva Fowler, they founded what would become St. Joseph’s AME Church. Their first sanctuary was a simple brush arbor: four posts anchored in the earth, a roof of branches, and an earthen floor. Soon, a log structure replaced the arbor, becoming Durham’s first school for African Americans, known as the Freedmen’s School, and establishing education as inseparable from faith and community.

Our History

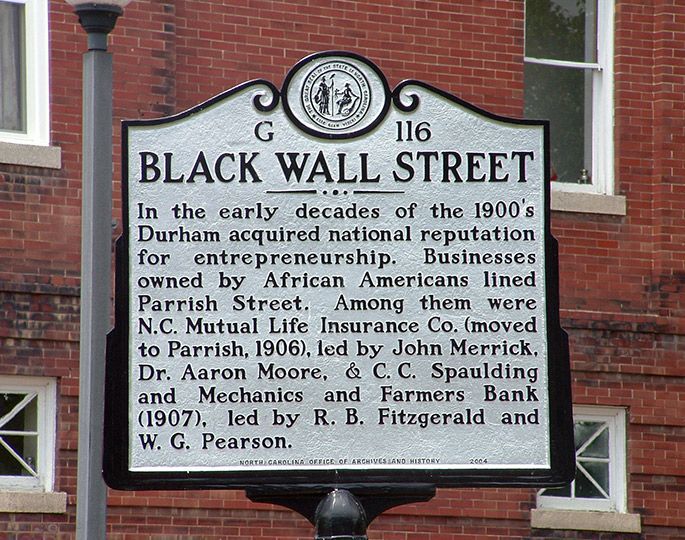

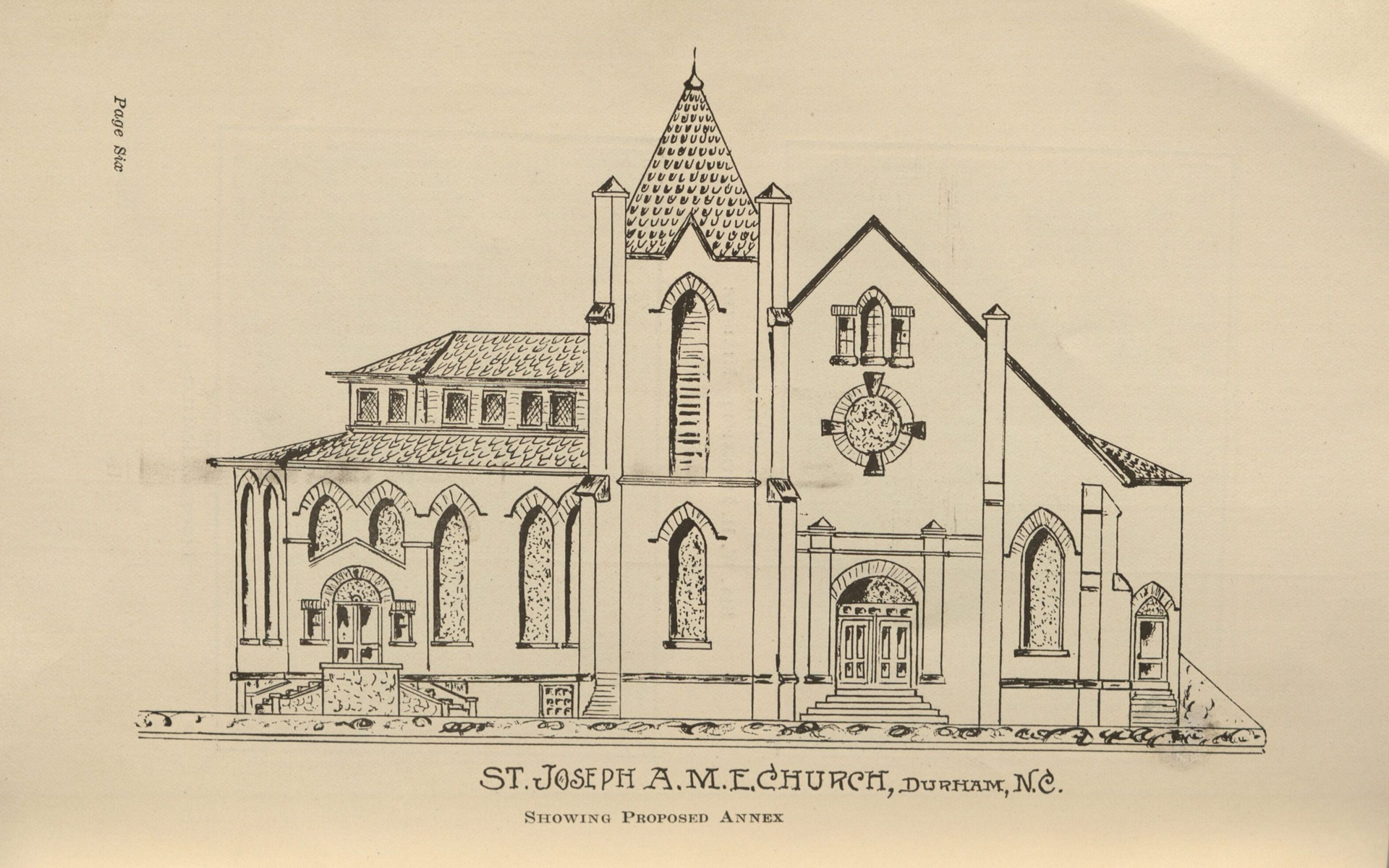

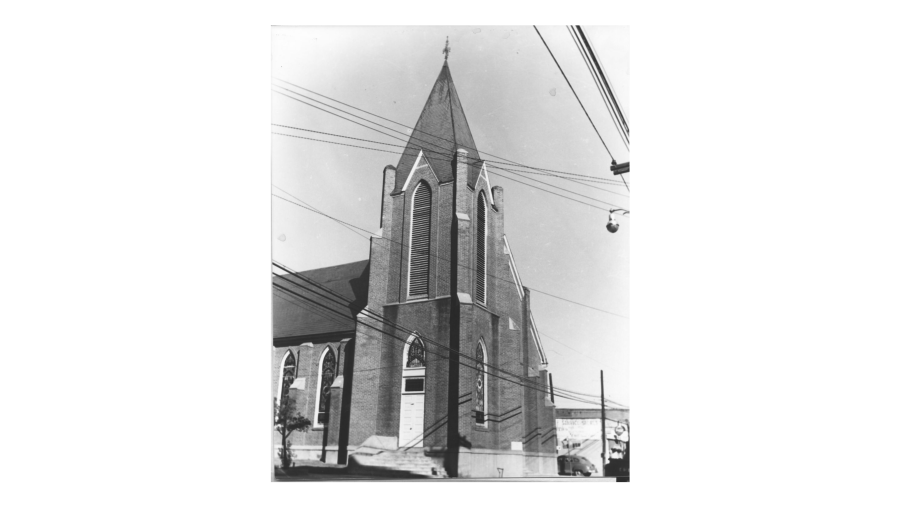

Under successive leaders, the congregation expanded, replacing each structure with one more substantial, reflecting both the growth of the community and its determination to claim dignity and visibility in a segregated city. By the 1890s, St. Joseph’s had emerged as both a spiritual and architectural landmark. The congregation commissioned Samuel Leary, an architect whose brief tenure in Durham produced several of the city’s notable late-19th-century buildings, to design their new sanctuary. Leary brought a bold, eclectic vision: the building married the weighty presence of Richardsonian Romanesque with the verticality of Gothic Revival and the balanced symmetry of Neo-Classical design. Bricks sourced from the Richard Fitzgerald brickyard, combined with Leary’s stylistic ambitions, created a structure that embodied the community’s aspirations and asserted African-American presence in a city still defined by racial hierarchy.

Inside, St. Joseph’s has always been more than a building.

A pressed tin ceiling, painted turquoise and gilded in gold, stretches overhead, its coffers, floral bosses, and intricate moldings drawing the eye upward. A two-tiered Art Nouveau chandelier hangs like a jewel above the center aisle. Stained-glass windows commemorate individuals whose contributions shaped the church, while the spire bears a vévé of Erzulie, linking Hayti to the African diaspora and the revolutionary spirit of Haiti, the first Black-led republic. Even the small details—the pews, the second-story gallery, the electric fans installed by E.N. Toole in the 1930s—reveal ingenuity, care, and communal investment.

For decades, St. Joseph’s was at the spiritual and social center of the Hayti neighborhood. Urban renewal in the 1970s threatened the sanctuary, but the St. Joseph’s Historic Foundation rose to preserve it. When the congregation moved to a new home, the building reopened in 1975 as the Hayti Heritage Center, a space dedicated to cultural preservation, education, and community. Since then, it has hosted countless concerts, civic events, and celebrations, cementing its role as a stage for Black creativity and scholarship—from jazz legend Dexter Gordon to local punk bands, the sanctuary has welcomed voices that reflect the vibrancy and diversity of the community.

The late 1990s brought a careful restoration, funded by public investment and guided by the Freelon Group. Slate roofs were repaired, ceiling trusses restored, and the upper balcony expanded, creating a sanctuary with a 450-person capacity that honors history while serving contemporary audiences. Today, Hayti stands as a living testament: a place where African-American history is preserved, where the arts thrive, and where the community continues to define its future from a foundation built on resilience, ingenuity, and brilliance.